The Lady at 74

Illustrations: Vidya Gopal

A version of this story first appeared in Grandma's Tales, an anthology edited by Lalita Iyer. You can buy the book here so you can get the beautiful stories from the other authors too.

*Chummoter = 74 (in Gujarati)

------------------------------------------------------------------

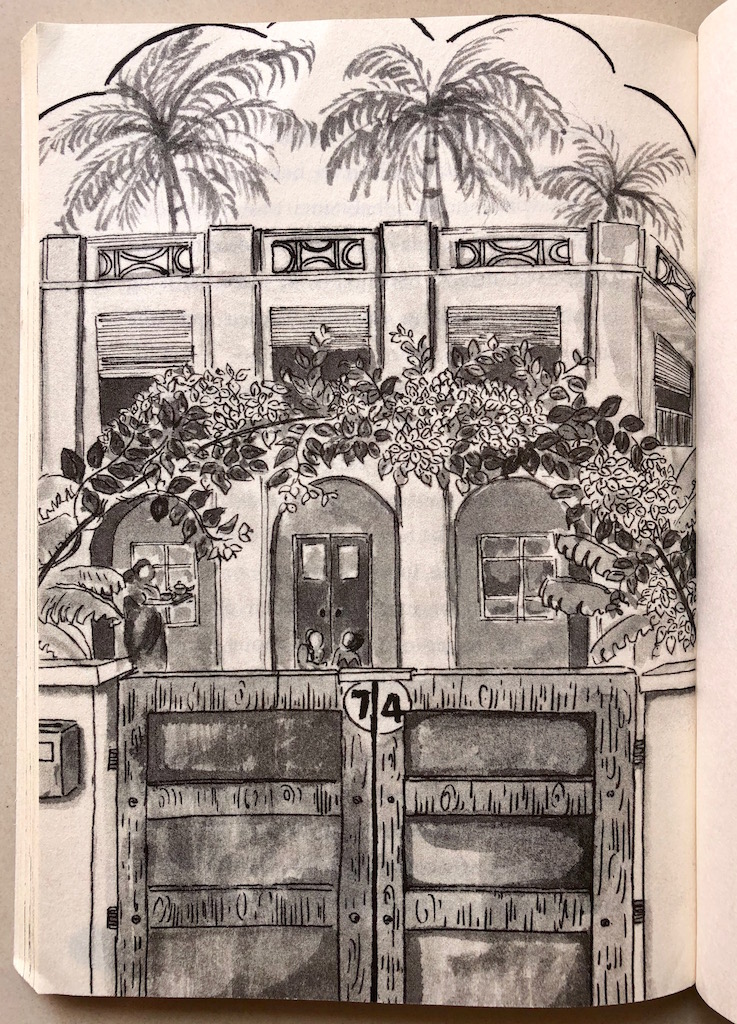

The house sat at the corner of the lane.

It was a big house.

Two-storeyed.

Old.

Lived in.

A little courtyard sat in front of it.

A garden with an archway,

Covered with green creepers

and pink Bougainvillea flowers.

The gate was two doors with a latch.

One that you swung shut from the top.

These doors had a number in a circle.

74.

Chummoter.

All the memories I have of my grandmother – Ma as the kids knew her, Bachen to the rest – have their roots in this number.

She was the lady of 74.

Married as young as 18, Ma lived at Chummoter in Ahmedabad, for most of her adult life. And this house began to stand for everything she was: warm and forgiving, selfless to a fault, ever open, never judging.

Under her reign, 74 became a living breathing being, like Ma herself.

Very quickly after she made her home here, to the battalion of family members from across the world – and there were enough to form an army (this was a Gujarati family after all), 74 became a place –

to roost, to study,

to idle away vacations,

to lodge at through college,

to recuperate from disease or love

(depending on the affliction at the time)

to find a comforting lap to weep/ sleep into,

to feed, to scavenge,

(For the kitchen at chummoter was never closed),

to drop messages for each other,

to sit on the swing and ponder,

to meet potential suitors under a watchful chaperone.

Essentially, if there was a question rising in the family’s collective conscience, it was largely believed that the answer would reveal itself in Chummoter’s loving embrace.

Her years at 74 were her most formidable. Ma owned the family not because she cooked and cleaned for them – but because of her heart, which was as big as Chummoter, if not larger. She loved intensely, without context, and threw open her home to everyone who needed it.

Born at the dawn of the First World War, Ma lost her parents when she was just a child. Raised by her older sister, and a child of a difficult period in history, she also had a ringside view of India’s freedom struggle. In that, Ma’s understanding of a world that was rapidly changing honed her defences and ensured that she grew up to be a survivor, one that adapted to changing landscapes.

She was an accomplished athlete at 14 and her lanky frame and cascading ankle-length hair were the envy of the girl’s sorority. She dreamed of being a sportsperson when she grew up but her time on the playground, along with her education was cut short when she was married off at 18.

She never complained about this swift and almost casual dismissal of her dreams except once. She had attended a meeting for and by a women’s organisation in Ahmedabad. She had dressed for the occasion, delighted to be attending, excited and hopeful, for the first time in her life, to be part of a cohesive group of peers, sharing and participating in matters that concerned women. There, she walked up to an acquaintance and attempted to strike up a conversation, but the woman looked at her and walked away without saying a word. She came home in tears, and said of the slight, just that one time, ‘If I were educated, if I knew what to say to people, this would not have happened.’

She never spoke of it again, but it is possible that these events further shaped her attitude towards her four children (two daughters, including my mum; and two sons) and grandchildren (four boys and me). After she lost her husband, she often came to stay with us. She delighted in my independence, never faulted my clothes, my nights out, my almost breathless dedication to work. She sent both her sons abroad to study and when both married American citizens, she accepted their decisions despite the societal perceptions of that time and in truth, her own wishes.

When 74 was sold, Ma lost a part of herself. No longer able to manage the large space by herself, it was decided that Chummoter would have to go. As news spread across continents, the family collectively mourned the loss of their childhood. There wasn’t a single child in that cluster who had not at some point called Chummoter home and didn’t feel a proprietorial claim over it.

Ma was aware, when she signed the sale that home would never mean the same again. She moved into a flat in Ahmedabad (alone until her health allowed it), fatefully enough, just minutes away from 74, and much later with us in Bombay. The last few years of her life in our house were the toughest for her, and I believe her health had little to do with it. 74 had been hers, and she had belonged to it. Her independence, her comfort, her memories were all swathed in 74’s gorgeous square tiles, in the garden with the jamun and mango trees, in the photographs of her large family on the mantle, in the ever open kitchen, in the backyard chowk.

Here in Bombay, she floundered. Her health deteriorated and her will rebelled harder, stronger. I believe something similar was happening with 74, as it was being systematically razed to the ground, to make way for something else to come up in its place. At home, I, with the impudence of youth, was not good to her during her final years. I was short with her, impatient with her age, and at the end, resentful of her illness.

As her body failed her, she fought harder. When her legs weakened, she walked more, prompting us to buy her a walker, which spent more time being walked behind her by one of us, than her deigning to use it. When her muscles slowed, she cleaned more, worked harder, once giving us a fright as we came home to see her, at the age of 85, balancing precariously on a stool to clean the top shelf of a cupboard. It was Diwali, she said, as if this should have been obvious to us.

The more she rebelled against her dying body, the more agitated I found myself. What if she fell? What if she broke her hip? Couldn’t she see that my mother was still reeling from the shock of my father’s untimely death? Why couldn’t she just behave herself? I saw only the old, stubborn woman, unable to come to terms with the restrictions her age and illness demanded. I forgot about the powerful matriarch, the years that she had triumphed, the experience and wisdom she had and the steely strength of her resolve.

These are all traits I had always wished for, but when faced with them hidden in the garb of an ailing grandmother who should (did) know better, I fought to tame them. I thought I knew better. I studied much, learned nothing and I failed her, repeatedly, in her last years, and I have never forgiven myself for it.

Ma breathed her last in Bombay at the age of 94, surrounded by loved ones, our relatively large apartment almost unable to fit in the army of heartbroken Chummoter alumni who came to pay their respects.

It is a testament to the relationship Chummoter had with us that even today, when we talk about Ma, we see her in that house, in her crisp white cotton saris that always smelled of chandan and fresh soap, or in the kitchen, serving hot crumpled rotis, dripping with ghee to grandchildren who sat in a line in the chowk, or helping the domestic help with their studies, paying for their children’s careers, sitting on the swing on the front porch, and running her kingdom from her throne.

Today, when I pass 74, it is no longer Chummoter. A tall, apartment complex, it is almost ugly in its transformation, sterile, non committal, even aloof, but I’d like to believe that somewhere in the foundation, Ma’s steely resolve and her unending ability to love lives on, and that the house still sighs when it thinks of the Lady at 74.

In the memory of a matriarch and her home, and all the childhoods -- especially her oldest son Girin's -- that contributed to this note.